| SHADOWS ON THE WALL | REVIEWS | NEWS | FESTIVAL | AWARDS | Q&A | ABOUT | TALKBACK | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Shadows off the beaten path Shadows off the beaten pathIndies, foreigns, docs, revivals and shorts...

On this page:

ICEMAN |

A TRIP TO THE MOON |

YULI

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| See also: SHADOWS FILM FESTIVAL | Last update 27.Mar.19 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Iceman Der Mann aus dem Eis Review by Rich Cline |

|  Spinning a story from the 1991 discovery of a 5,300-year-old body in the Alps, this film is set out as the first revenge thriller in human history. Gorgeously shooting in rugged locations, writer-director Felix Randau uses elaborate long takes and striking historical authenticity to tell a story that feels very familiar to anyone who has been following Liam Neeson's career over the past decade. In a Neolithic mountain settlement, Kelab (Vogel) is the leader of his clan, so he and his wife Kisis (Wuest) adopt an infant when its mother dies. One day while out hunting, Kelab's village is ransacked by Krant (Hennicke) and his two thuggish cohorts, and everyone except the baby is killed. So Kelab sets out to find the people who murdered his family and to regain the mystical wooden box that represents his tribe's religious heart. Along the way, he gets some help from an elder (Nero) and his randy, flute-playing daughter (Anna F). The characters speak an early Rhaetic language, but there's no need for subtitles as the plot is as old as the hills. Randau stages the action skilfully, with arrows firing like bullets and a grisly sense of death and destruction. Even so, the narrative sometimes feels comically modern, layering present-day European family values plus some Taken-style vengeance on this prehistoric community. But this gives the story a driving sense of momentum. The filmmaking makes it tricky for actors to add nuance, because dialogue is unintelligible and they're obscured by hair and fur. Also, the camerawork is grand rather than intimate. Because Kelab is saddled with a crying baby as he begins his quest, Vogel is able to add some nice textures to the character. Otherwise, it's tricky to understand who people are as Kelab encounters them along the road, although Randau does make it clear, somewhat simplistically, who's good or bad, while also showing some balance in the cycle of revenge. Grittier than similar prehistoric adventures like Quest for Fire (1981) or Apocalypto (2006), this film has a superb sense of forward motion as Kelab pursues Krant's gang further up into the mountains, where someone is going to end up encased in ice. Because of the way the story is told, 96 minutes feels much longer, but the progression of the plot and the spectacular changing landscapes hold the interest, as does Randau's relentlessly inventive direction. These make it involving and memorable, even if the plot feels rather blunt.

|

| A Trip to the Moon Un Viaje a la Luna Review by Rich Cline |

|  dir Joaquin Cambre prd Diego Peskins scr Joaquin Cambre, Laura Farhi with Angelo Mutti Spinetta, Leticia Bredice, German Palacios, Angela Torres, Luis Machin, Luca Tedesco, Micaela Amaro, Tiziano Duarte, Federico Venzi, Julian Ponce Campos, Justino Mutti Spinetta release US/UK 22.Mar.19 17/Argentina 1h27 RAINDANCE FILM FEST

|  A witty, visceral filmmaking style puts the audience into the mind of a teenager in this sharply observed coming-of-age drama from Argentina. First-time director Joaquin Cambre builds the characters inventively, revealing deeper attitudes through skilful imagery and sounds. Then in the final act, the plot stalls badly, wallowing in the premise's gimmicks rather than making the story resonate. In Buenos Aires, Tomas (Spinetta) is a skinny 14-year-old who feels increasingly uncomfortable everywhere he goes, especially around his parents (Palacios and Bredice) or his antidepressant-dealing shrink (Machin). So he dreams of going to the moon, and begins transforming his bedroom into a space capsule with plans for his parents and his siblings (Juliana and Coco) to join him. Then through his telescope he spots neighbour Iris (Torres) and when they meet she becomes intrigued by his ideas. Although her boyfriend (Venzi) just sees Tomas as another kid to bully. "Why do people say that the sun goes down," Tomas asks as the film opens. "Is it so hard to understand that it's we who move?" As he begins to question the world around him, the way he withdraws from friends and family is strikingly realistic, even as it turns absurd. The fantasy liftoff sequence is particularly remarkable, taking Tomas on a journey into his own psychological issues while revealing a long-hidden secret. That said, the sequence makes less and less sense as it continues. Performances are somewhat heightened, as each character has one salient personality trait. At the centre, Spinetta is compelling as a rather gloomy kid, although he's not easy to sympathise with when he gives in to his obsession. Bredice has a standout role as an over-involved mother who always seems on the verge of exhaustion. And Torres has the most subtle character, a popular older girl who is jaded but also compassionate, which kind of makes her feel more like part of the fantasy than the reality. As the film progresses, problems emerge in the narrative, partly because some of the bigger twists seem anticlimactic, while the central metaphor is both indulgently overused and increasingly underdefined. This means that Tomas' internal odyssey begins to go off the rails, widening out into the visual extravagance rather than finding a more engaging personal connection. So in the end, it feels like there isn't much to Thomas' story. And the way Cambre deals with some very dark themes feels a little glib.

|

| Yuli Review by Rich Cline |

|  dir Iciar Bollain scr Paul Laverty prd Andrea Calderwood, Juan Gordon with Carlos Acosta, Santiago Alfonso, Keyvin Martinez, Edlison Manuel Olbera Nunez, Laura De la Uz, Yerlin Perez, Mario Sergio Elias, Andrea Doimeadios, Cesar Dominguez, Carlos Enrique Almirante, Yailene Sierra, Hector Noas release Sp 14.Dec.18, UK 12.Apr.19 18/Spain 1h55

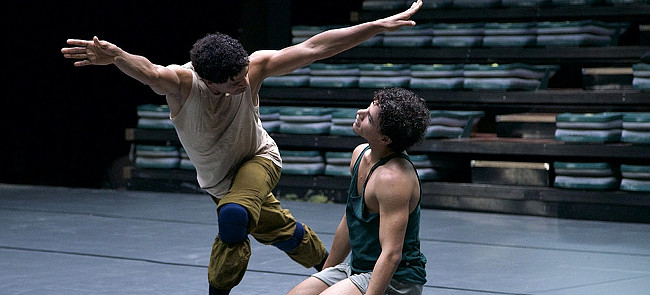

|  Cleverly framing Carlos Acosta's autobiography No Way Home with dance, politics and glorious Cuban scenery, director Iciar Bollain reunites with her husband, screenwriter Paul Laverty, to tell a sweeping life story that finds its soul in a jagged father-son relationship. Along the way, it also touches on race, colonialism and dreams of a better life, all of which resonate through the drama and Acosta's breathtaking dance work. Returning to Havana to stage an autobiographical show with his dance company, Carlos (playing himself) remembers his childhood as a street urchin called Yuli (Nunez) whose impoverished father Pedro (Alfonso) spots something special and forces him to go to dance school. Yuli isn't thrilled about this, as he'd rather become a football player, but every time he drops out, the strict Pedro and his tenacious teacher Chery (De la Uz) convince him to return. As a teen, Yuli (now Martinez) finds fame in Europe while continuing to grapple with his identity. Laverty's script doesn't shy away from the darker side of Carlos' relationship with his father, tempered by the compassionate presence of Carlos' mother Maria (Perez). But Pedro drives the story, reminding Carlos that his nickname comes from pre-colonial folklore, and that his grandparents were born into slavery. Visually, the contrast is perhaps a little too obvious between sun-drenched, big-skied Cuba and cramped, drizzly London. But this adds weight to both Carlos' homesickness and his surprise that he seems to be the only Cuban who wants to live there. Each Carlos is excellent, starting with Acosta, who cleverly underplays himself, keeping emotions just under the surface while expressing himself through his body. Dancer Elias plays him in choreographed sequences, and has his own communicative, liquid physicality. Meanwhile, Nunez brings cheeky alertness to the young Yuli, while Martinez adds passion for his craft amid swirling emotions. Both are just as expressive with their physicalities. The film a feast for the eyes, which helps the material brim with resonance. Acosta's journey is genuinely inspirational, partly because he was so reluctant to follow his dream, and it's refreshing to see a movie biopic that avoids sentimentality while maintaining a sense of momentum. It's also packed with much more far-reaching issues that also allow Acosta's story to touch on Latin American history, US political meddling and the European art scene. In other words, it beautifully captures both this hugely gifted man and the world he has so indelibly altered.

|

See also: SHADOWS FILM FESTIVAL © 2019 by Rich Cline, Shadows

on the Wall

HOME | REVIEWS | NEWS | FESTIVAL | AWARDS

| Q&A | ABOUT | TALKBACK | | ||||||||||||||||||